Description of the ACL (Anterior Cruciate Ligament) – or, as it is called in animals – the CCL (Cranial Cruciate Ligament)

Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury

If your dog has been diagnosed with a torn ACL (anterior cruciate ligament) then most likely your veterinarian has suggested some form of surgical correction for this problem. Your vet has probably told you that you have surgical options and may have referred you to an orthopedic specialist to have surgery performed.

Unfortunately, we veterinarians sometimes speak in ways that leave you confused, making it difficult for you to make appropriate decisions for your pet. I would like to try to explain to you, in plain English, what is involved in an ACL (anterior cruciate ligament) injury and its repair.

We need define our terms so we can understand the problem better

In canine patients, the ACL is properly called a CCL, or cranial cruciate ligament. The term ACL refers to the same structure, but in humans. Your veterinarian may refer to it as an ACL because most people have heard of athletes with torn ACL’s and understand what part of the anatomy we are speaking of. From here on out, I’ll be using the proper term, cranial cruciate ligament, CCL.

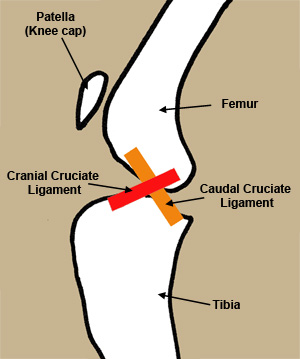

The knee joint (the joint where the CCL resides) is properly called the stifle joint. The stifle joint is composed of three major bones; the femur, the tibia, and the patella. Those three, in humans, are your thighbone (femur), shin bone (tibia) and knee cap (patella). The ends of these bones are surrounded by cartilage, the slippery stuff that allows for movement. They sit together in a fluid called joint fluid, and there is a seal around the joint called a joint capsule.

Inside the joint sits the CCL (cranial cruciate ligament) and another ligament called the caudal cruciate ligament. They form a cross shape, hence the name cruciate (meaning cross). This is important later when explaining joint function.

Also in the joint are two shock absorbers called meniscus. When you see an X-Ray of a stifle joint, the femur and tibia appear to be separated by space, but they are not. The femur sits on top of the meniscus. The meniscus is not visible on an X-Ray. For that matter, ligaments are not visible on an X-Ray either- so you cannot see the CCL on an X-Ray.

Let’s now explain the function of the stifle joint

The stifle joint is a complex joint; but I will simplify it so that its function can be understood. First, compare the stifle to a hinge that can only swing two ways, forward and backward. The center of the hinge is inside of the stifle joint. The forward swing is called extension, and occurs during weight bearing. The backward swing is called flexion and occurs during the non-weight bearing, or swing, phase of gait motion.

As everyone knows, when you walk, only one foot is on the ground at any one time. Now most importantly, to keep the femur (thighbone) in alignment with the tibia (shin) during motion are the cranial and caudal cruciate ligaments. These two ligaments, in the shape of an X, or cross, maintain appropriate contact between the two bones. The illustration shows the location of both ligaments.

Healthy Cranial Cruciate Ligament

The CCL attaches in the back of the femur and comes forward to attach to the front of the tibia. The caudal cruciate ligament attaches on the front of the femur, and goes backwards to attach to the back of the tibia. Where they cross each other is the “hinge” point.

Continue to “What Happens when the CCL Ruptures?”

Pingback: My girl slipped and fell and is now limping. - Doberman Forum : Doberman Breed Dog Forums

Pingback: kneeinjury | pregnancy date predictor